That time NCCU waxed an all-white Duke team during the Jim Crow era

Basketball in the state of North Carolina looked very, very different in the 1940s. The shorts were short, dribble moves were non-existent, and many of the best players in the state were barred from competing at the highest levels of the sport due to Jim Crow-era segregation.

Durham, 1944

In March of 1944, segregation was still the law of the land in Durham. The Royal Ice Cream sit-in was still more than 13 years in the future, people were forced to use separate but definitely not equal facilities, and black athletes weren’t allowed to compete in the NCAA or NIT tournaments.

At the time, Duke had won three Southern Conference championships in the previous five years and would go on to win it again in the 1944 season. Coached by Cameron Indoor namesake, Eddie Cameron, the Blue Devils were in the early stages of building the powerhouse program they would come to be.

Meanwhile, just across the tracks and through what used to be a thriving center of black businesses and culture before it was sabotaged by racist government policies and actions, a 28 year-old John McLendon was building a powerhouse of his own at then-North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University).

“We could’ve beaten anyone”

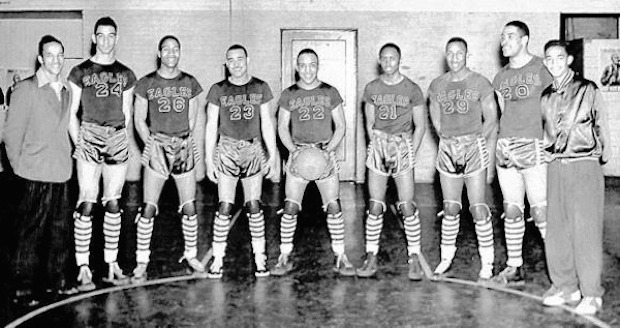

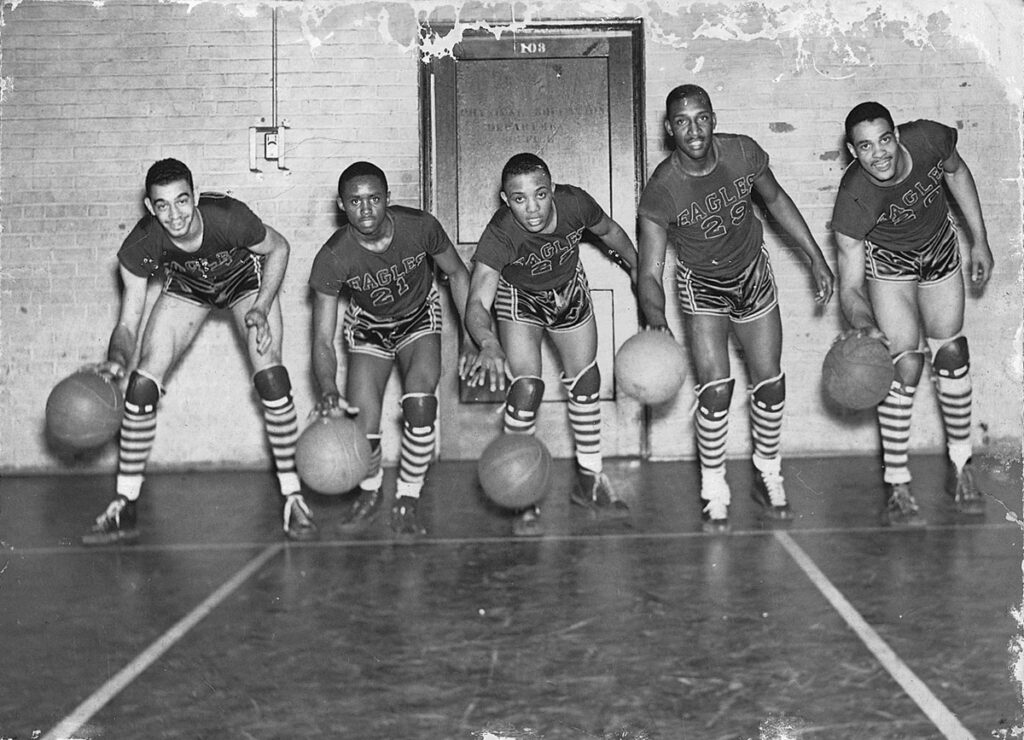

The Eagles of 1944 ran an offense that wouldn’t look out-of-place in today’s game. Standout players Aubrey Stanley, Henry “Big Dog” Thomas, Floyd “Cootie” Brown, James “Boogie-Woogie” Hardy fronted a fast-paced, high-scoring attack that would make Mike D’Antoni proud.

McLendon, a Hall-of-Famer and inventor (seriously) of the fast-break offense, full-court press, and four corners offense, recalled that at the time, “We could have beaten anyone.”

However, due to segregation and severe racial tension, the Eagles had no way of proving that.

A dangerous game

To give you an idea of just how bad things were at the time, that same year in Durham, a black G.I. had been killed on a city bus by a white driver who didn’t like the speed with which he was moving to the rear.

The idea of NCCN and Duke playing against each other wasn’t just novel, it was actually dangerous. Police at the time were responsible for maintaining the “color line” and those that broke that line faced severe legal and social consequences.

When McLendon proposed the game, it raised a lot of questions, but a few of their players were all in. Some of Duke’s players were not fans of segregation. Jack Burgess, a Duke guard from Montana, was chased off of a Durham bus with a knife by a white driver for objecting to the seating laws.

With several players on board and pride on the line, Duke’s medical school team, thought to be the school’s best, accepted the challenge.

“We thought we could whup ’em,” said Duke forward David Hubbell. “So we decided to find out.”

And find out they did.

“They’re just men like us”

Both schools kept the upcoming game a secret. They decided to play on Sunday morning when folks would be at church. Players hid themselves underneath their letter jackets and on the floor of cars heading to the game. No spectators or media were allowed.

“The secret game” tipped off around 11 AM on March 12, 1944. What followed is based on witness accounts, as the game doesn’t exist in any record books.

Both teams got off to a slow, nervous start. Turnovers, shots clanking off the rim. Then Duke got into the game and scored off of screens and set plays. Soon, the Eagles picked up steam and tightened up their defense. They pressed the ball, picking up steals and throwing long, outlet passes down the court to force the pace.

“About midway through the first half,” said Stanley who was just 16 at the time, “I suddenly realized: ‘Hey, we can beat these guys. They aren’t supermen. They’re just men like us.’”

From that point on, Stanley and the Eagles never looked back. NCCN broke out their wide-open, breakneck style of play that wouldn’t become popular for decades and Duke had no answers.

What was a close game early on became a rout. NCCN ended up thrashing Duke 88-44. Durham had its city champions, definitively.

Epilogue

John McLendon would go on to become one of the greatest, most innovative basketball coaches of all time. Duke would become Duke.

It would be eight years until the landmark Brown v. Board decision, 20 years before the Civil Rights Act officially ended segregation in North Carolina, and 21 years before Duke or any other ACC school had a black player on the roster.

But that’s not to say that The Secret Game didn’t change anything. A few days after the game, Burgess wrote to his family in Montana:

“Oh, I wonder if I told you that we played basketball against a Negro college team. Well, we did and we sure had fun. And I especially had a good time, for most of the fellows playing with me were Southerners. . . . And when the evening was over, most of them had changed their views quite a lot.”

Editor’s note: While we absolutely love partisan pettiness here at BBQ, BBALL, ETC. and Duke getting blown out is always cause for celebration, the 1944 NCCN team would have almost certainly obliterated whatever teams UNC or NC State would have been fielding at the time, too.

No Comments